The Year of Wonders

How the green comet changed everything

It was the year when mermaids swam in the Thames and the Martians sent an ambassador to the Court of St James’s. The year when Greek Gods rubbed shoulders with the hoi polloi over tea at the Dorchester, and a dragon made its nest atop the Royal Albert Hall with apparently every intention of hatching it.

A century and an eternity ago, sometime between the Victorian and Edwardian eras, lies a forgotten chapter of history.

It was a time when our world overlapped with fabled lands of the imagination. When high society rubbed shoulders with Venusian diplomats in the tea rooms of the Savoy, when Greek gods were invited to dine at High Table in Oxford colleges, when transatlantic telephone wires hummed with the voices of drowned sailors, and when dragons flew over the white cliffs of Dover.

How did this come about, and why was it forgotten?

The first is easy to answer. Comet Meadowvane appeared in the sky and mysterious green lights were seen at night. Not long after, strange things began to happen. The first reports could be explained away as mass hysteria, but not for long. Soon it became clear that the world had changed.

The magic had come back.

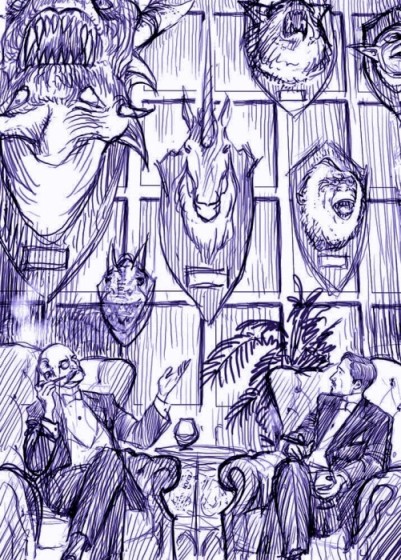

At first, fantasy started to impinge only gradually on everyday life. In an oak-panelled room in the heart of London’s clubland, a renowned big-game hunter lately returned from the North-Western Provinces called together a select group of friends, closed the curtains, and displayed the stuffed head of a yeti among his latest trophies.

At first it was all happening far away, in the unmapped corners of the world. But steamers sailed from those foreign ports every day. By February, everybody had a friend or a relative who had seen something fantastic with their own eyes. Walking in the woods, you might catch a glimpse of a dappled hide in the sunlit groves. A unicorn? A satyr? By night, something clattered the dustbin lids and searched in the coal cellar with tiny goblin hands.

And even if you whisked the curtains shut and tried to pretend everything was normal, pretty soon the rising tide of fantasy was impossible to ignore. As the green comet grew bigger, the supernatural would come knocking at your door. A centaur in a postman’s cap. A dwarf offering to sharpen your knives. A genie with wishes on hire-purchase.

Since the fantastic was clearly here to stay, people soon started to embrace it as something new and exciting, like electricity and motor cars. If you were moving house, for example, who better to help with carrying your furniture than a giant?

Especially handy when your room is right at the top of the house.

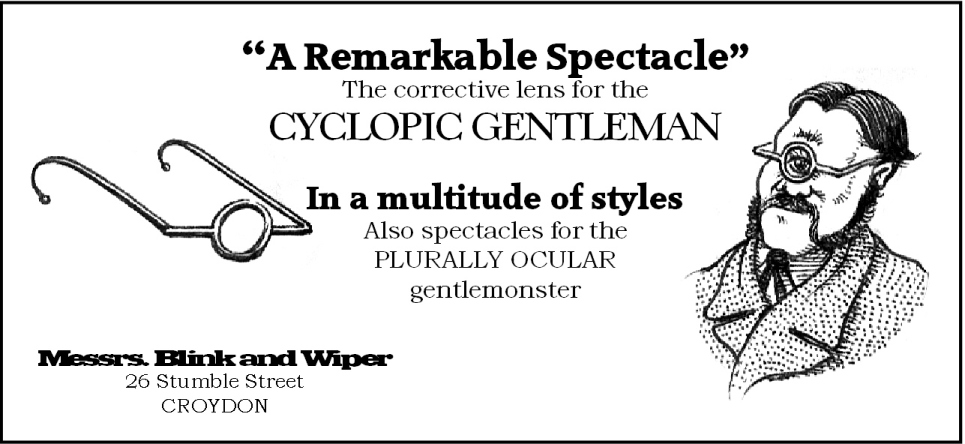

As fantasy and reality began to merge, of course there were bumps on the road. It was only to be expected. The Royal Mythological Society in Bloomsbury was deluged with urgent letters enquiring about points of etiquette. As Dr Clattercut put it: ‘The question of which fish-knife to use becomes quite vexed when your dinner guest is a mermaid. Does a Martian ambassador rank above a marquis? When a ship is sinking, does a cherub count among the women and children? Should you open a door for a lady vampire?’ In assimilating the fantastic, the Edwardian middle classes began to invest it with their usual anxieties.

Lower down the social strata, at that staple of working class entertainment, the music hall, the existence of real magic started to give some of the acts a little bit too much of an edge:

More than one member of the audience stomped to the box office to demand his money back, complaining that the whole pleasure of a conjuring act lay in trying to figure out how it was done. It was a fair point. When the imaginary becomes real, what happens to the imagination?

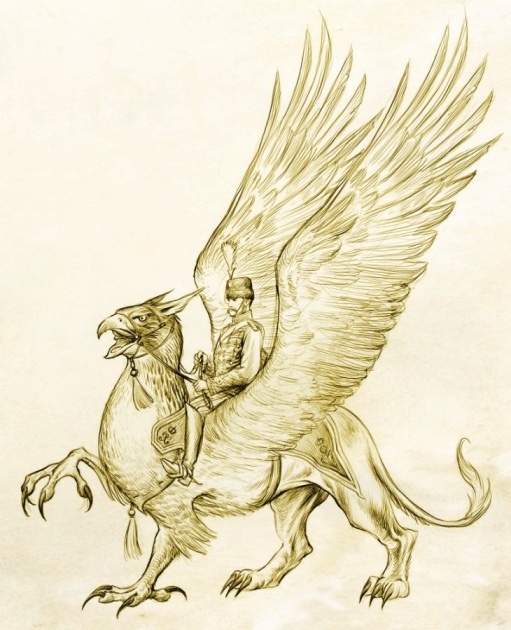

As the initial novelty wore off, as liminality gave way to commonality, many of these problems went away. You expected and welcomed the fairies at the bottom of the garden. In the suburbs, a shrubbery without its own dryad was a sorry sight indeed. Above Hyde Park flew the air battalion of the Household Cavalry on their more-or-less tame griffins. And over in the City of London, rash was the banker who tried to handle his investments without a telegraphic printer feeding him hourly horoscopes and auguries on tickertape feed.

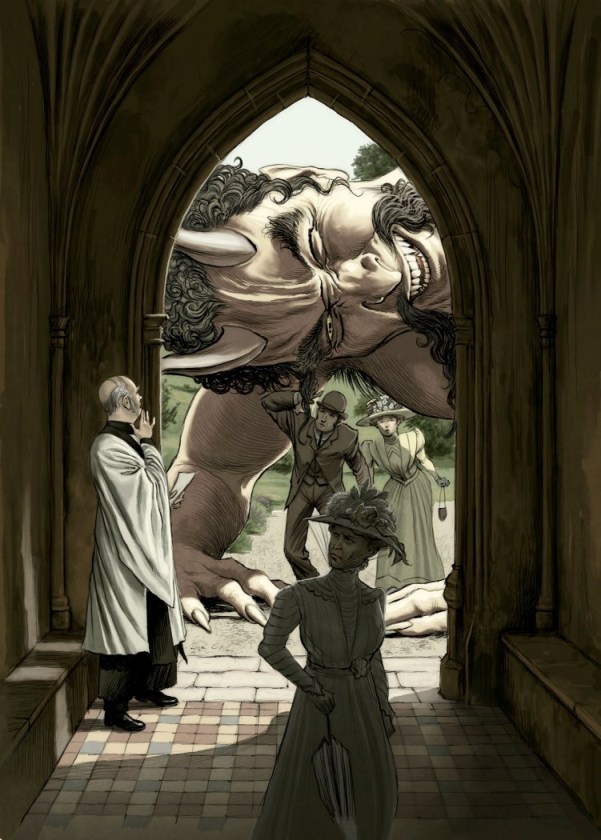

And with the best will in the world, and even given the most sincere and Christian of welcomes, there remained very definite obstacles to prevent the more pagan deities from attending Sunday service.

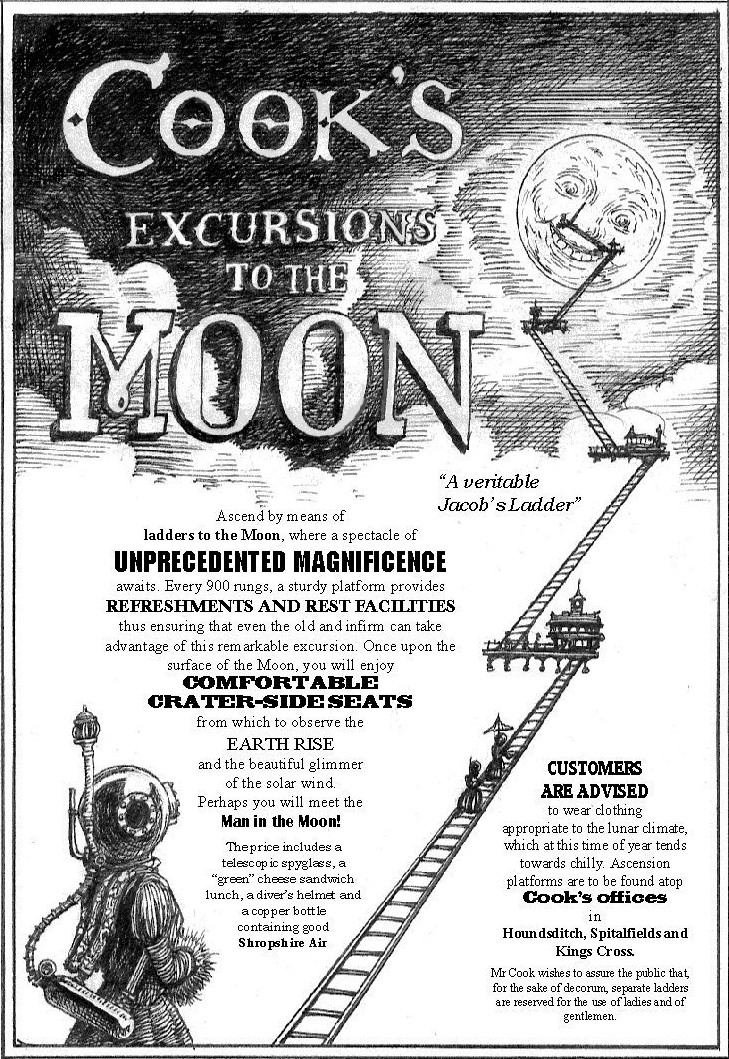

For the more adventurous, there were now undreamed-of challenges and frontiers. Lunar climbers could be seen each night, clutching rope, axes and crampons, rising in hot air balloons to attempt the difficult dark face of the Moon.

Intrepid armchair explorers set off in search of Shambhala, Xanadu, El Dorado, Atlantis and Fiddlers’ Green, confident of finding two or even three such places within walking distance of their hotels.

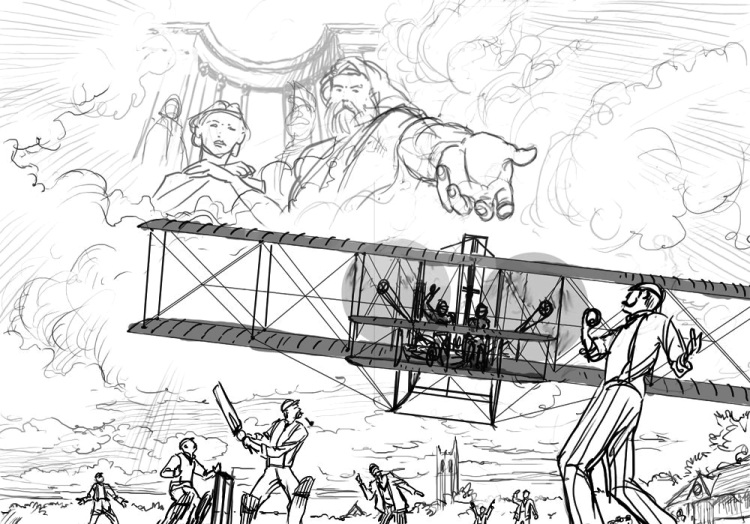

Not only in the fields of sport and exploration, but in business too, it was a time when risking all could reap great rewards. Isambard Kingdom Brunel won the contract to rebuild Bifrost as an iron suspension bridge over the clouds to Asgard. He employed pegasi to lift sections of the framework into place. A scholar at Cambridge wrote in high dudgeon to The Times with the objection that Pegasus was the name of a unique mythological creature, not a species. Brunel replied jauntily that it was the popular imagination that held sway under the green comet’s glow, not whatever may happen to have been handed down in academic books. Other correspondents agreed, but unwittingly Brunel had planted the first seed of doubt. The creatures who now shared our parks and trains and seasides, whom one might pass on the street, invite to dinner, or even woo – these came not from another realm, magical but definite, sealed off from our own except when the green comet’s light pierced the barrier. Rather, they had bubbled up out of our own subconscious.

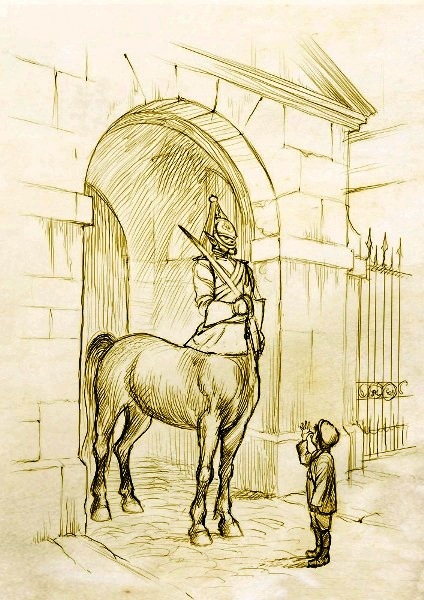

But it was not yet the height of summer, and few paused to question the changed world around them. Certainly not the cavalry commanders who, impressed by the use of griffins in the Air Brigade, now took steps to enlist another mythical creature in the newly-restructured Light Brigade.

A field officer of the time remarked: “Thank heavens for these centaurs we were issued with in the spring. They’re the macaroni, I can tell you. Much nippier than our old nags used to be. Just as well when some damned fool tells you to charge a Russian artillery emplacement. Er, you won’t print that bit, will you?”

Eventually fantastic and mythological events were so common that they became part of everyday life, not only accepted but intimately familiar. Few even remembered that the world had not always been this way. It was the aestas mirabilis – the Summer of Marvels.

Ordinary people, aliens, monsters and fantastic creatures mingled to watch the comet on Midsummer Night. Passing between the Earth and the Moon, it filled the entire sky and its light was bright enough to allow one to read the classified advertisements in a newspaper. Magic was so strong on the air that many said they could taste it – an intoxicating scent that incited a million inimitable experiences that night.

Few gave any thought to what would happen as the comet swung around the sun and began to travel back out into the depths of space. As it faded, surely the fantastic creatures and things whose existence it had ushered in would also start to dwindle? Yet dying is not the mirror image of growing. Having been given life, who would wish to see it fade away within a single year?

But as autumn gave way to winter, the magic was to take a darker turn…