Patterns in the Fire: writing for comics

Inspiration is the most important thing for a storyteller. But while you can train your brain to make those inspirational leaps, if you don’t think that way to begin with then it probably can’t be taught. And what about other tools of the trade: style and voice and a sense of pacing? Those you have to hone – and, like the arrow in Zeno’s paradox, even one lifetime may not be enough to hit the target of complete mastery.

On the other hand, there are a lot of basic rules that you can learn in an afternoon. It’s said that Gregg Toland, the director of photography on Citizen Kane, gave Welles a crash course in Cinema 101 on the first day of filming. Not everyone masters the basic rules right away – and it takes even longer to discover how you can break them – but here are a few that I’ve found useful when writing comics.

Planting seeds

A story is not a house, ready built for the reader to walk into. It’s more like an organism that has to grow in the reader’s mind. To make it grow properly – that is, to keep the reader with you – you’ll need to plant seeds. A very obvious example is when you embed a hint of an idea (often a plot idea) early on so that the reader is prepped for it later.

A seed can be planted to carry the burden of complex discussion of a theme which would interrupt the story if put later. For example, District 9 drops a number of subtle references into the narrative so that we don’t need to wonder at the end where Christopher Johnson’s planet is or how he came to be stranded on Earth in the first place.

Another example: in the “Crush” episode in season five of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, very early on we hear Willow explaining to Buffy and Tara that Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame wasn’t really a hero because his decisions were not driven by a moral compass: “He did good things for love of Esmerelda, but that doesn’t make a hero”.

Later in the story, Buffy is arguing with Dawn about hanging out with a dangerous vampire like Spike. Dawn says “You used to date Angel,” and Buffy says that’s different, Angel had a soul. To which Dawn replies: “And Spike has a chip. Same difference.”

Because of this, much later at the end of the season, we’ve already covered the theme of what makes a hero. The seeds of the debate are already planted. Is it enough to do good things, or must you do them for a moral reason? Without those earlier scenes, the writer would have had to cram in ten minutes of exposition right at the climax.

There are two levels of seeds. The first is at the basic level of craft, the screws and washers that hold your plot together. The second is a more subtle foreshadowing of themes and things to come.

The two types are used well by Edna O’Brien in her BBC adaptation of her own short story Mrs Reinhardt. The main character, who is staying at a French rural hotel, has a valuable emerald necklace that she wears most of the time.

She meets an American who we suspect of stealing the necklace. However, at the end we learn that it was not the American who took it, but one of the hotel maids. There are two scenes that show the basic level of seed-planting: one where Mrs Reinhardt is delightedly swinging a pillow in her bedroom, letting off steam because she thinks she’s alone, when the maid comes in with breakfast and surprises her. In another scene, Mrs Reinhardt enters the kitchen to find the maid and the other serving staff fooling around until the chef brings them to order.

Those two scenes do the basic craftwork. They tell us that the maid has a key and could enter the room at any time, and also that the maid may act very serious and deferential when on duty but she is an individual who in private is frivolous and playful like any young girl.

But that’s not all. In the second of the two scenes, O’Brien goes further and plants the higher level of seed. As the maid is going past her out of the kitchen, Mrs Reinhardt points at a plate of fruit and says, “May I?” and the maid says, “Of course, madame; they’re all hanging out there in the garden to be picked.” And thus the writer introduces, very subtly and in retrospect, the notion that the maid might regard things that are lying around as there for the taking.

Just the facts

Exposition – the conveying of facts to the reader – is the red-headed stepchild of every writer’s working day. You need to get the information across. You need to give only as much information as the reader really, really needs. You need to make it emerge naturally from the story. Most of all, as with everything else, you need to make it entertaining.

It’s not always a problem. “Luke, I am your father.” That’s got enough of an emotional punch that Vader can just say it – though notice how the fight scene had to build up to Luke’s physical defeat before this truly terrible news could be imparted to maximum effect.

Pure plot information, though, is a real headache for the writer. It doesn’t carry any intrinsic emotional charge to connect it to the characters; it’s just some boring detail about what time the bank guards complete their rounds, or what will happen if the control codes aren’t entered into the computer. Stick it in as a plain statement of facts and it’s like shoving a stick into the spokes of a bicycle wheel. Instant momentum killer: suspension of disbelief goes sailing over the handlebars and ends up nursing a bruise from which your narrative may never recover.

I saw a good example of how to handle pure plot exposition in the first season of Desperate Housewives. One of the four leads had some major piece of local gossip that she needed to impart to the others. But, when she tracked them down they were in the middle of a coffee morning with a bunch of other neighbors who she didn’t want to let in on the secret. So she gets them out into the kitchen on some pretext and closes the door. Now she’s imparting this info to her friends (and us, the viewers) but she’s having to whisper – and she’s got to say it all fast before the others come back in. The tension, though completely contrived, distracts us enough that the exposition slips by quite entertainingly. We hardly even notice we’ve just been fed a shovelful of facts.

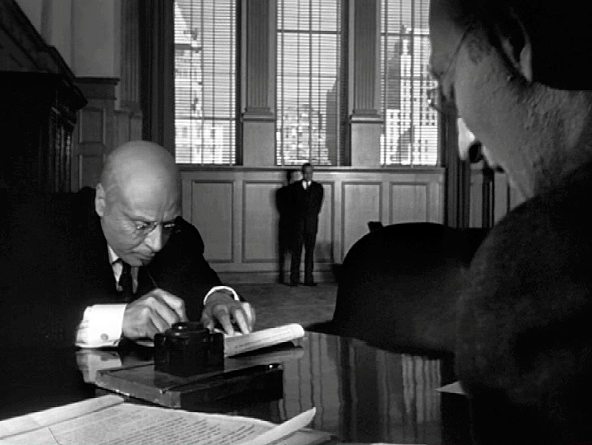

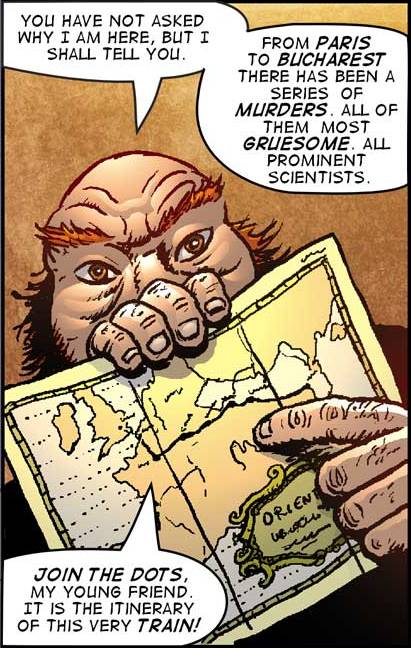

The most overtly expositional scene I’ve had to write for Mirabilis was in issue #3 (“Standing on the Shoulders of Giants”) when Inspector Simeon tells us about the murders that have brought him aboard the train. The information is essential to the whodunit subplot that will embroil Estelle in more than a little trouble later. At the same time, it’s just a bunch of facts that the reader has no reason to care about right now.

So look at everything that actually goes on in that scene. Jack is riding high after saving the day with Stephenson’s Rocket. He’s cornered by Simeon and goes along with it in order to cover for Gus, who is sneaking back onto the train. Simeon drones on but Jack is distracted. They’re in a narrow train corridor and other people are squeezing past – specifically Sir Archibald Whitmead, who thereby gets to overhear what Simeon is saying.

Jack shows no more interest in Simeon’s theories than we readers have any reason to – but when he walks off, we stay with Simeon and Caitou. And now we learn that Jack’s nonchalance has aroused Simeon’s suspicions. (That’s another piece of exposition, covered this time by Simeon’s amusing sense of self-importance: “My instincts are buzzing like a beehive on an August day.”) Ah, so it turns out that the exposition that Jack (and we) barely listened to could land him in hot water. Now we know the facts and we’ve been given a reason to care.

Confound expectations

As you unfold a story, most of the time the reader will be there before you. They’re read a lot of comics, they’re wise to the clichés, and they’re taking note of those seeds you’re planting. But here’s the rub. If the scene simply goes the way the writer obviously wants it to, the reader is going to kick against that. To enjoy a story it’s necessary to suspend disbelief, and every predictable moment risks bringing disbelief right back into focus.

We’ll look at a couple of examples of how it works. First from the movie Vertigo:

Scotty (Jimmy Stewart) is waiting for Judy to return from her makeover. We expect him to go “Gosh!” the moment she shows up dressed as Madeleine, her hair now dyed blonde, wearing the gray suit he picked out for her, and so on – but something still isn’t quite right. It’s only after he gets her to pin her hair back just the right way that he can finally see her as Madeleine.

And this one from The Last King of Scotland:

Dr Garrigan (James McAvoy) spins a globe and decides he will go wherever his finger lands. Of course, we know he’s going to Uganda. Only that’s not where his finger lands. The first time he stops the globe at Canada, but immediately decides that won’t do. He wants adventure. He spins it a second time, and then he gets Uganda.

These scenes both use a kind of narrative sleight of hand to overcome our natural resistance to being spoon-fed a story. While we are concentrating on what we expect to happen, we are not expending our skepticism on any other outcome. So when the scene plays, as it were, out of the magician’s other hand, we are surprised into full acceptance.

The twist you don’t see coming

This is related to the confounding of expectations, but it’s not quite the same. When you’re getting to the climax of a story, simply piling on more and more difficulties for your hero won’t do. The audience sees a string of things that have to be dealt with and they project forward: “Once the hero has done A, found B, discovered C, it’s all going to be sorted.”

Why is that bad? Because you need for the reader to wonder what happens next. If they can see where it’s all going, they may as well put down the book and go do something else. So you need to throw in something completely from left field – a development that takes the reader or viewer by surprise.

Here’s an example from the movie of My Favorite Martian. Tim has to prevent the TV broadcast of a video of Uncle Martin which would prove the existence of aliens on Earth. Meanwhile Martin himself is going to pieces – literally – and his spaceship (which is counting down to self-destruct) has been reduced in size with Tim’s girlfriend inside and left in the garage, where the neighbor picks it up for a jumble sale. With a bit of fast-paced rompy action, all these problems are neatly fixed. They get the video, Martin is reassembled, and they catch up to the neighbor’s car and retrieve the “toy” spaceship. Whew! Exactly what we expected. But then, just at the moment of triumph, the government agents who were chasing them earlier turn up and zap Martin and Tim with a tranquillizer gun, and take them off to a remote army research base. Now we have no idea what’s going to happen next. The stuff we foresaw all got resolved. This is a new development we didn’t see coming. And the story shifts into high gear as a result.

That’s how it works on the overall plot level – the “break into three” as Blake Snyder puts it. But stories are fractal, and the same principle applies within one scene. In James Saxon’s book Red Chamber, the hero, who is wanted by the police, has to sneak on board a London subway train at Sloane Square. The writing team’s initial plan was for him to climb over the wall (the Tube line is open to the air at Sloane Square) but of course that on its own wouldn’t strike the reader as much of a challenge. So the hero climbs the wall from the street, but it’s a big drop to the platform on the other side, and he has to get down by edging along a narrow iron pipe to a point where he can jump. On top of that it’s snowing, so not only is the pipe slick with ice, but he has to be careful not to dislodge snow so that the police look up. Then, to stay out of sight, he jumps onto the roof of a Tube carriage, intending to swing down into the carriage just as the doors are closing…

But all of that stuff is just the sleight of hand to set us up for the real twist in the scene. Getting onto the Tube train roof calls for nerve and athleticism, and is undoubtedly all quite difficult for anyone without spider powers, but it’s still only a “skill roll”. The reader knows that the writer can just decide to have the hero succeed. What we need is to see the hero come up with a solution to an unexpected problem, preferably under extreme pressure where we can’t imagine being able to do it ourselves in the time available. And that’s what happens next. There’s a policeman right there on the platform, so the hero can’t get inside the carriage after all. The doors close. Okay, he thinks, I’ll ride on the roof to the next station. So he (and we) start to relax…

Too soon! Because he now sees there is only about a foot’s clearance on the tunnel. Scrabbling back, he falls between two carriages and holds onto the “bellows” between the carriages with his shoes almost touching the tracks. Then at the next station he climbs onto the platform and makes his getaway. And boy, do we feel he’s earned it.

Show don’t tell

My wife, though an author under her own name and a ghost writer with over one million books sold, also does a lot of literary consultancy, editing and story polishing. One day, looking over her shoulder as I brought her one of many morning cups of tea, I saw another editor’s notes she’d been sent. The other editor had been working on a short story and had come across this passage:

The editor had seized on this as a failure to “show not tell”, and gave an example of how to expand it into a 250-word scene in which Max introduces the narrator to Russian cigarettes for the first time.

That advice was completely wrong. Because the writer had shown, and very elegantly too in only 37 words. The telling version of that passage would have gone something like this:

There are two writing rules that often, as here, get confused. “Show don’t tell” is a corollary of Forster’s “Only connect!” (that’s the most important storytelling rule of all) and it means that the writer shouldn’t just communicate a fact, but must also make us feel it. “The room was very big,” is just phoning it in. “The room was as big as a cathedral nave” at least evokes a mental image, though possibly, “The room was so big that it made Jeff feel like a child being led into a classroom for the first time” is better because more personal.

The other rule, which I suspect the editor who commented on that short story was thinking of, is “make a scene of it”. This is a lot less of a hard and fast rule. In There Will Be Blood, for example, we might expect a scene of Daniel Plainview dragging himself back to town after breaking his leg in the shaft where he’s just struck oil. Instead, Paul Thomas Anderson, the writer/director, cuts straight to Plainview on a stretcher watching the men he’s hired tally up his newfound wealth.

You’ve got to be a little bit careful about breaking the “make a scene of it” rule. Audiences can be mistrustful of things that happen off-stage and that they only get to hear about later. It’s safe enough if the scene you’re skipping would only have covered routine details that the reader or viewer can fill in for themselves. For example, after the cliffhanger at the end of issue #2 of Mirabilis we cut straight to Jack in Paris. You didn’t need to see him pack a bag, collect his ticket from the Royal Mythological Society, and catch a boat. All that was implied. But if we’d missed out the earlier scene of Gus escaping from Bedlam and just referred to it in a later episode, you’d have wondered if the info was kosher. And quite right too.

Show don’t tell comes in when, for instance, Jack balks at shaking Gerard’s hand before the duel. Or later, on the beach at Selsey, when he remembers himself as a child watching his parents go off in a boat. Hopefully you empathized more with Jack then than if he’d simply stated his feelings – though indeed, dialogue can show instead of tell:

FRODO This is what?

SAM If I take one more step it’ll be the farthest away from home I’ve ever been.

(Frodo gives Sam a pat on the shoulder.)

FRODO Come on, Sam.

How to set up a threat

The most effective threats are the ones you set up in the course of your story. That’s why, if you’re going to have your characters menaced by a gun, you should ideally show your audience what the gun can do. Yes, they already know that guns can smash vases and blow limbs off. But audiences tend to treat a story universe as an independent microcosm. (Which is reasonable enough, as in some story universes – eg the world of Wile E Coyote and Road Runner – you can get blown up by dynamite and just end up with singed eyebrows.)

So you need to show them what the rules of your story universe are. They will accept these rules very readily, by the way. Audiences are actually hungry to find out the rules you’re using.

Suppose you have a bunch of characters enter a very spooky place, but they have a talisman or a protector with them. Spooky as the place is, they are safe as long as they have the talisman and don’t do anything dumb. If you set it up properly, you only have to have the characters lose the talisman and suddenly your audience will be in a real panic. They’ll believe there’s a credible threat in the haunted house or whatever it is because, with that talisman, you set up the rules necessary to achieve suspension of disbelief. More accurately, you didn’t suspend their disbelief at all. You actively engaged their willingness to believe.

In case this all seems a tad abstract, consider a bunch of little furry-footed chaps going through a really ancient, dark, eerie, goblin-infested cavern complex. But it’s okay because they have the world’s most powerful wizard with them. Except then they come up against a really nasty monster and the wizard deals with it but he falls down a bottomless chasm. And now they’re alone. In the dark. And suddenly Moria seems like a very dangerous place indeed.

– Dave Morris